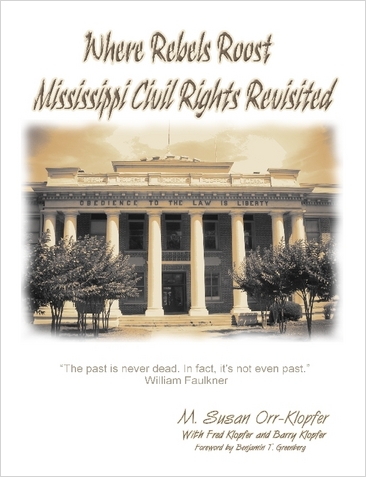

Where Rebels Roost... Mississippi Civil Rights Revisited

Where Rebels Roost... Mississippi Civil Rights Revisited

by Susan Klopfer, MBA

With Fred Klopfer, Ph.D. and Barry Klopfer, Esq.

Foreword by Benjamin T. Greenberg

Printed: $29.17 Download: $11.25 (order)

June 27, 2005

Following this week’s conviction of Edgar Ray Killen on three charges of manslaughter for the 1964 murders of civil rights workers James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman in Neshoba County, Mississippi, it has been typical to hear triumphant declarations such as this one by Jim Prince III, editor of The Neshoba Democrat: “We pronounce a new dawn in Mississippi, one in which the chains of cynicism and racism have been broken and we are free, free at last, thank God Almighty we are free at last!”

It is at best delusional and at worst a deception to view Killen’s conviction as meaningful expiation for Mississippi’s notorious racist crimes. To begin with, there are nine other living suspects whom the prosecution did not pursue. More to the point, however, are the lines of culpability that extend well beyond Killen and well beyond the Neshoba County klavern of the White Knights. We must look instead to the racist state government of Mississippi of the 1950s, 60s and 70s and to federal complicity in the state’s crimes. We will not read much about this in the news reports about the Killen trial, but we can learn a great deal of what we need to know in Where Rebels Roost. Susan Klopfer is determined to tell the truth about Mississippi and about America and she does a great deal of that truth telling in the pages of this book.

Klopfer’s book is one of the first to look closely at the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, the state spy agency whose anti-civil rights activities included providing intelligence and money to the Klan. Klopfer also examines the roles of powerful people like Senator James O. Eastland, who received regular reports from the Sovereignty Commission. We cannot begin to fathom the nature of racial repression in Mississippi without knowing what Klopfer reveals in her book. It is no exaggeration to say that Mississippi of the 1950s and 1960s was a totalitarian police state.

Klopfer also follows the money, showing how the lines of culpability lead into the offices of New York industrialist Wycliffe Draper, whose Pioneer Fund fueled Mississippi’s fight against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and provided millions of dollars for the private “academies,” established to keep white children out of integrated schools after Brown v. Board of Ed. (More recently, the Pioneer Fund financed the research for the controversial book, The Bell Curve, a best selling, racist tract published in 1994.)

America’s greatness rests on the countless brave souls, like Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman, who have stood up for justice on its soil, in the name of this nation's own democratic principles. The nobility of these American citizens is not always understandable without some measure of the evils that they have faced. Klopfer's truth telling brings careful scrutiny to the long and ongoing history of racial repression in Mississippi and the resistances to it.

Where Rebels Roost tells a story that begins with the kidnapping and enslavement of Africans and continues through the American Civil War, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, and the white supremacist backlash against it that continues into the present, along with current, anti-racist community activists. Klopfer's story of Mississippi and America casts new light on events that will be familiar to many readers, and it tells important stories that have never been told before.

***

The focus of this book is the Mississippi Delta—the northwest portion of Mississippi, wedged between the Mississippi and Yazoo Rivers, with some of the most fertile soil on the planet. The Delta has brought great wealth to white planters and industrialists who built their Southern society on the exploitation and impoverishment of African Americans. The Delta is also the home of a rich Blues tradition, running from Charlie Patton on through Pops Staples, which Klopfer artfully places in its proper context, amid the many currents of history that she describes. Klopfer dispels the dual myths that there was little Klan activity and little native civil rights work in the Delta. There has been much of both, and her drive to describe and understand them is another of Klopfer’s major accomplishments in this book.

By writing the history of civil rights in a particular region, rather than a study of an organization, particular activists or an individual political campaign, Klopfer demonstrates the real diversity of civil rights activity in the state and in the nation. In these pages, there is much to be learned about SNCC, SCLC, COFO, NAACP, Black Panthers and MFDP—and about the Colored Farmers Alliance (nineteenth century), Delta Ministry, Deacons for Defense and Justice, Mississippi Freedom Labor Union, Republic of New Afrika and Black farm cooperatives, like Fannie Lou Hamer's Freedom Farm Cooperative.

In these pages, you will read about crusaders for freedom and equality with familiar names, like Medgar Evars, James Meredith, Fannie Lou Hamer, Bob Moses, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Ella Baker. You will also read about Amzie Moore, Aaron Henry, Birdia Keglar, Mae Bertha Carter, Cleve McDowell, Margaret Block and Sam Block—and many other local Delta people who fought for civil rights before there was outside interest in the early and mid 60s and after SNCC, CORE. COFO and SCLC organizers had largely left the scene.

Outside help was crucial to civil rights activity in Mississippi, but the local activists shaped the Movement in ways that are often forgotten. For example, Klopfer reminds us that when SNCC’s Bob Moses arrived in Mississippi in the summer of 1960 he was thinking in terms of the sit-in movement that had galvanized him to leave his New York teaching job and become an activist. Ella Baker’s friend, Amzie Moore, of Cleveland, Mississippi first conceived of the voter registration campaign that became the centerpiece of Freedom Summer. Unlike other local NAACP leaders, Moore welcomed outside help, but he was a guiding force from the start.

***

Susan Klopfer’s long view of the history of civil rights in the Mississippi Delta brings us on a march through two centuries of race riots, individual racial murders and genocidal policies against African Americans. There are the widely rehearsed murders of Emmett Till, Medgar Evars and Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman and Fannie Lou Hamer’s riveting testimony at the 1964 Democratic Convention of how she was cruelly beaten for registering to vote. But Klopfer’s march for truth and justice also takes us through less well-known territory: nineteenth century race riots in Minter City, where as many as one hundred African Americans were murdered and many more beaten and injured; the possible massacre of as many as 1200 African American soldiers at Camp Van Dorn by the US Army in 1943, with involvement from US Senators Eastland and Bilbo; the untold numbers of adults and children who starved to death in Leflore County, when, from 1962 to 1966, the Klan and the White Citizens Council pressured county officials to cut off distribution of federal food subsidies, in retaliation for Black voter registration activities; the murders of Birdia Keglar and Adeline Hamlet in 1966, James Keglar, son of Birdia (three months after his mother), Daisy Savage and her grandson in 1973, Cleve McDowell in 1997—and many others. In her work on these last six individuals, Klopfer describes cases that beg to be investigated. Included among Klopfer’s appendices is a list of over fifty civil rights slayings in Mississippi and a table of the state’s lynching statistics.

After you read this book, the conviction of one eighty year old man for the murders of Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman can seem like nothing but a farce. If we want to break “the chains of cynicism and racism,” Where Rebels Roost shows us where to begin. And it is, indeed, only a beginning. In an email, Klopfer told me that many old people in the Delta keep their own lists of people who were killed. As she put it in another email to me, “Even the countries of Germany and Chile have done a better job accounting for the evil done in those countries and making amends. Apologies are due many families.”

With wry irony, Susan Klopfer notes, “Senator Eastland was born nine months after the lynching [of Luther Holbert and his wife (name unknown) in 1904], which was led by Eastland’s father, a pharmacist and planter. Since lynching was often accompanied by celebrations and parties for the white persons attending, perhaps Senator Eastland was conceived on this occasion.” This may just seem like some well deserved spit in the eye for a vicious racist, but Klopfer’s comment also speaks to the tremendous benefits many whites have reaped from a system that devalues African American lives. Where Rebels Roost raises important and troubling questions about an all too wide array of systemic racial inequalities in the Mississippi Delta.

Why were African American children suffering from clinical malnutrition and why were prenatal care and dental care unheard of for Blacks, while white Mississippi planters received farm subsidies many times larger than those given out in other states? A1968 study, which Klopfer cites, found that “In 1966, there were more payments of $50,000 in each of eight Mississippi counties than in the states of Iowa and Illinois combined.... In the seven states of Iowa, Illinois, Nebraska, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Ohio, 165 producers received checks of $25,000 or more, as compared with the 194 in Mississippi alone who received payments of $50,000 or more.” The disbursement of these monies should have been contingent on proper implementation of the flagship Head Start programs that were begun in Mississippi and effectively shut down by 1967, through, “investigations, surveillance, firings, audits, press attacks, closures and threats.”

Why were there heavily African American Delta towns like Tunica, with no water or sewer connections—in 1985? Why were Delta Pride catfish processing plants allowed to earn nearly three quarters of a billion dollars in annual sales while African Americans labored in their unsanitary sweatshops with no holidays or benefits in the 1990s?

Why in 2005 is Mississippi’s infant mortality rate the highest in the US with 10.5 deaths per one thousand infants under one year old across the state and up to 18 infant deaths per thousand in parts of the Delta? The national infant mortality rate is 6.8 (which is nothing for the richest nation in the world to be proud of).

***

In a post-9/11 America, Susan Klopfer’s revelations about Sovereignty Commission surveillance should serve as a dire warning about the dangers of allowing government to revoke our civil liberties and spy on its citizens with increasing impunity and diminishing oversight. Consider this summary of the Intelligence Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2004 from Kim Zetter:

Under the law, the FBI does not need to seek a court order to access such records, nor does it need to prove just cause.

Previously, under the Patriot Act, the FBI had to submit subpoena requests to a federal judge. Intelligence agencies and the Treasury Department, however, could obtain some financial data from banks, credit unions and other financial institutions without a court order or grand jury subpoena if they had the approval of a senior government official.

The new law (see Section 374 of the act), however, lets the FBI acquire these records through an administrative procedure whereby an FBI field agent simply drafts a so-called national security letter stating the information is relevant to a national security investigation.

And the law broadens the definition of "financial institution" to include such businesses as insurance companies, travel agencies, real estate agents, stockbrokers, the U.S. Postal Service and even jewelry stores, casinos and car dealerships.

The law also prohibits subpoenaed businesses from revealing to anyone, including customers who may be under investigation, that the government has requested records of their transactions. (Wired News, Jan. 6, 2004)

There is no telling what the FBI is doing with such invasive powers, granted with the full authority of the law. The Sovereignty Commission, whose surveillance powers were acquired largely by fiat, was able to have similar access to citizens’ financial records. Cleve McDowell, who was murdered in 1997, earlier attracted the Commission’s attention when he was the first African American to enter law school at the University of Mississippi in 1963. Klopfer writes:

The [Sovereignty Commission] investigator [Tom Scarbrough] was sent back to Drew on June 4 and 5 to find more dirt on young McDowell. From R. D. Cartledge, “cashier of the Bank of Drew,” Scarbrough learned that “a Negro female school teacher gave Cleve McDowell a check for $10 payable to McDowell on May 27…. McDowell endorsed the check to Medgar W. Evers [who] in turn cashed the check at a service station in Jackson.” This fact was duly reported back to the Sovereignty Commission.

Scarbrough was not able to learn why “Jessie Singleton Gresham” gave McDowell the $10 check. He tried to talk once again to McDowell’s father and when he “could get no one to respond to my knock of their front door” he “journeyed over to Oxford … to observe his admittance to the University School of Law on June 5, 1963.”

Kim Zetter noted that “Bush signed the [intelligence] bill on Dec. 13, a Saturday, which was the same day the U.S. military captured Saddam Hussein.” It is important to note the parallels between the present war in Iraq and the Vietnam War, which was one of the backdrops for the Civil Rights Movement. In his essay “Highways to Nowhere,” Wallace Roberts, who was a Freedom School coordinator in Cleveland and Shaw, Mississippi, recalled that at “the first memorial service for the three civil rights workers, held just a few days after the Gulf of Tonkin incident that marked the beginning of the Vietnam War, Bob Moses, the head of the summer project, said simply, ‘The same kind of racism that killed these three young men is going to kill thousands of Vietnamese.’”

Roberts also recalled last year’s fortieth annual memorial for Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner, at the rebuilt Mt. Zion Church, which had been bombed by the Klan on June 16, 1964, setting in motion the events that led to the murders of those three brave, young men:

Dave Dennis, one of the leaders of Freedom Summer, said that it doesn't really matter now what happens to a bunch of old men even in the name of justice. What matters now is the injustice still being done to the black children of Mississippi: Governor Barbour recently asked for a cut of more than $200 million in state funds for public education. This in a state that already ranks at the bottom nationally in per pupil spending.

I was able to shave a couple of hours off my driving time thanks to the lavish investment in slick new roads by Barbour and his predecessors, but that savings comes at the cost of the continuing intellectual enslavement of the state's black children.

Drive on, Mississippi, you're on a highway to nowhere.

(Click here to order Where Rebels Roost.)