In no sense do I advocate evading or defying the law, as would the rabid segregationist. That would lead to anarchy. One who breaks an unjust law must do so openly, lovingly, and with a willingness to accept the penalty. I submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust. and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law. (Martin Luther King, Jr., "Letter from Birmingham Jail," April 16, 1963)

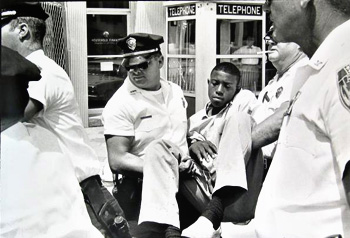

Eddie Brown calmly being carried off by the Albany, GA police, 1963 (Photo by Danny Lyon)

What do MLK's Letter from Birmingham Jail and the SNCC lunch counter sit-ins have to do with recent controversial digital protests in support of Wikileaks? Last week, an online activist group known as Anonymous brought down the MasterCard and Visa websites, and purposely slowed down PayPal, in retaliation for the decisions of those companies to stop doing business with Wikileaks. Anonymous called these actions Operation Payback.

Deanna Zandt has written a great report on the flurry of discussion that has erupted in reaction to the assertions recently made that the tactic for bringing down the credit card websites, known as distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, is a legitimate form of civil disobedience. (And since I first started writing this post, an excellent further discussion has been unfolding in the comments to Deanna's post.)

Deanna explains:

A quick lesson on DDoS for the unfamiliar: a group of people gets together and decides to render a website unusable. They do this by flooding the website’s server with so many requests that the server gets overloaded and either slows down, or stops responding altogether. A big important point: this is not hacking. “Hacking” generally applies to incidents where systems are actually broken into and data is compromised. DDoS doesn’t do this.

To use the case from this week, a group of activists called Anonymous (more on them in a second) decided to render, among others, Mastercard’s website unusable. This does not mean that credit card data was stolen, or that people were unable to use their Mastercards for purchases. It means that if you went to Mastercard.com, you got a message that the website was unavailable.

So, the question: is this a legitimate form of civil disobedience?

I got into the discussion on Twitter on last Friday night (12/9) with Liza Sabater, Josh Mull, Tom Watson and Erica George, and on Saturday (12/10), with Deanna and with Meredith Patterson.

On Friday night Tom's tweet caught my eye: "Taking down Amazon with DDoS is book burning." Josh bristled: "What books were MLK or organized labor burning? It's a sit-in, an occupation." I came down on Tom's side and said, "MLK and SNCC lunch counter sitins were prepared to go to jail. They didn’t do anonymous destruction." Liza saw the lunch counter and DDoS tactics as closely paralel; the Civil Rights Movement protestors "disrupted bness like DDoS," she said. Tom challenged the DDoS/sit-in analogy, saying, "Yeah, if the lunch counter sit-in volunteers carried sledgehammers and destroyed the joint...bad analogy." Josh sarcastically questioned the assertion that Anonymous is violent: "I hadn't heard all those companies were destroyed. That changes everything. What'd they use? C4? Plastiq?" "DDoS is more aggressive than sit-in tho," Erica pointed out; "it denies speech to the other party rather than just exerting it's own speech."

Erica's comment helped me start to understand my discomfort with Anonymous' tactics. Anonymous was responding to the silencing of Wikileaks with more silencing, rather than any kind of civil discourse or political demand. Following the attacks, according to The Guardian, Anonymous declared:

We will fire at anything or anyone that tries to censor WikiLeaks, including multibillion-dollar companies such as PayPal. ((In the days since I first started writing this post, I have not been able to find this statement anywhere except in the cited Guardian news story; I am therefore no longer fully convinced of its authenticity. Nonetheless there are plenty of similar statements in the @anonops twitter stream and elsewhere.))

Anonymous threats are the stuff not of freedom fighters but of cowardly night riders, who attack under the cover of darkness, and White Citizens Councils, who invisibly coordinate sanctions against perceived agitators. I'm not equating Anonymous with the Klan or White Citizens Council; in fact as I've found more of their official statements, I've come to respect their intentions. But the Operation Payback tactics are closer to those employed by the secret, vigilante defenders of white supremacy than they are to the methods of nonviolent resistance and Black liberation. As King stated in his Letter from Birmingham Jail, "One who breaks an unjust law must do so openly, lovingly, and with a willingness to accept the penalty." The person in the Wikileaks narrative who comes closer to this standard is Bradley Manning, who, in the posture of a whistleblower, knowingly broke the law, accepted the consequences---and now is paying an enormous price for it---in hopes that more truth and less secrecy will free the US from the destructive course it remains on.

I should pause here to make the distinction between DDoS as a tactic by itself and Operation Payback as a use-case by Anonymous. I am primarily focusing on the specifics of what Anonymous did and said rather than on DDoS writ large. Thus far, however, I am generally opposed to DDoS as a tactic. As Nathan Freitas commented on Deanna's post, "DDoS is a lazy form of civil disobedience, at best, and one the participants undertake with very little to no training or preparation for the potential consequences." Ethan Zuckerman has furthermore made a compelling point that DDoS is a destructive practice that can take many websites offline for weeks at a time, if not permanently.

On Saturday (12/10), before she'd written her blog post, I saw Deanna tweet, "I am FAR more worried abt corporations taking away my free speech than @anonops making paypal slow down;" I replied: "I question actions that are not accountable to a community or to the other side. How is that 'civil' disobedience?"

In her blog post, Deanna elaborated on her position:

Anonymous launched a DDoS attack against the websites of the companies that took away people’s rights to support a political organization. Many, myself included, consider DDoS in this context to be much like a sit-in in the offline world. The point of a sit-in is to render a building/room/service unusable for a temporary period of time. Sit-ins aren’t “legal”– you get arrested, and most activists who participate in them know this ahead of time and prepare for it....

In a case like this, who else do they need to be accountable to? Maybe I’m misunderstanding the question, which is why I wanted to take this part beyond the 140-character limit. An anti-war group that sits-in at a recruiting station is accountable to whom? Themselves, certainly. Are they accountable to the entire rest of the anti-war movement? The opposing side, in this case, the military or the police, can hold them accountable by arresting them.

Earlier in her post, Deanna defined civil disobedience neutrally, referring only to a Wikipedia, dictionary-like, definition, but clearly in talking about sit-ins, she is joining Liza and Josh in evoking the Civil Rights Movement legacy. In fact, in the longer statement, released by Anonymous on Thursday, they themselves made the connection overtly:

During the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, access to many businesses was blocked as a peaceful protest against segregation. Today much business is conducted on the Internet. We are using the LOIC to conduct distributed denial of service attacks against businesses that have aided in the censorship of any person. Our attacks do no damage to the computer hardware. We merely take up bandwidth and system resources like the seats at the Woolworth's lunch counter.

Civil Rights Movement leader Diane Nash speaks on the steps of the Neshoba County Courthouse, Philadelphia, MS, June 23, 2007, at a gathering of activists calling for justice for victims of civil rights era racial violence. (Photo by Ben Greenberg)

In the nonviolent practice that everyone is hearkening back to, accountability doesn't mean that you can get arrested---if you get caught. That's true anytime you break the law, regardless of your intent. Here's what's involved, according to Diane Nash, one of the chief architects of the student sit-in movement and of non-violent direct action as a tactic for defending and obtaining civil rights.

We felt that in order to create a community where there was more love and more humanness, it was necessary to use humanness and love to try to get to that point. Ends do not justify the means. As Gandhi said, everything is really a series of means.... Truth now for me has very little to do with being good or doing what's right. It's more relevant to me in terms of providing oneself and people around one with accurate information upon which to base our behavior and base our decisions....

I think another fundamental quality of the movement is that we used nonviolence as an expression of love and respect of the opposition while noting that a person is never the enemy. The enemy is always the attitudes, such as racism or sexism, political systems that are unjust, economic systems that are unjust, some kind of system or attitude that oppresses. Not the person herself or himself....

Another important tenet, I think, of the philosophy was recognizing that oppression always requires the participation of the oppressed. So that rather than doing harm to the oppressor, another way to go is to identify your part in your own oppression and then withdraw your cooperation from the system of oppression....

There is so much about the philosophy that people as a whole never knew, because what was reported in the newspapers was just the fact that the demonstrators were not hitting back or not creating violence. But there were five steps in the process that we took a community through. The first step was investigation, where we did all the necessary research and analysis to totally understand the problem. The second phase was education, where we educated our own constituency to what we had found out in our research. The third stage was negotiation, where you approach the opposition, let them know your position, and try to come to a solution. The fourth stage was resistance, where you withdraw your support from the oppressive system, and during this stage would take place things such as boycotts, work stoppages, and nonsupport of the system. (A Circle of Trust: Remembering SNCC, edited by Cheryl Lynn Greenberg, pgs, 19-21)

Comments by Anonymous about why they focused on some targets over others suggest some amount of investigation and education among the organizers but little involvement of the people enlisted to help perpetrate the DDoS attacks. As Nathan said in the comment I quoted earlier, "the lunch counter and bus strikers were against specific laws about those places and services. Gandhi refused to buy salt, show his papers, and so on, because he felt to do so was unjust and unfair." Anonymous' resistance was vague and general and veiled in anonymity and certainly did not involve related demands and negotiation towards some alternative state of affairs. The DDoS attack was more like vandalizing the storefront than sitting in. If you bolster censorship, prepare to be censored, was the gist of the Anonymous message. Payback.

When my conversation about this with Deanna was first getting started last Saturday, Meredith Patterson challenged my assertion that progressives shouldn't embrace Anonymous as a spokesperson for internet freedom. She pointed out, "voluntary groups will respond, accountable or not" and for her, perhaps more importantly, "there's not just one prog community; never has been. Personally, decentralised but cooperative action appeals to me more." There's a very rich conversation to be had about political movements and centralized vs. decentralized action and leadership. I can't detail it now, but SNCC was fundamentally a decentralized entity (contrary to assertions made recently by Malcolm Gladwell)---which was deeply inclusive and radically democratic.

Anonymous may have some similar appeal in its inclusive rhetoric that seems to invite us to join them and find power in numbers.

Anonymous is a spontaneous collective of people who share the common goal of protecting the free flow of information on the Internet. Our ranks are filled with people representative of many parts of the world and all political orientations. We can be anyone, anywhere, anytime. If you are in a public place right now, take a look over your shoulder: everyone you see has all the requirements to be an Anon. But do not fret, for you too have all the requirements to stand with those who fight for free information and accountability.

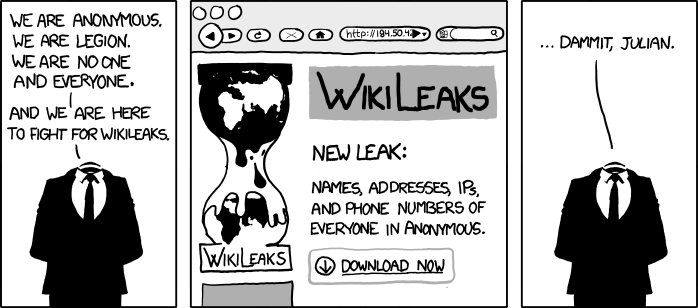

But there is a fallacy here. XKCD lays it bare.

The disruptive power of Anonymous lies in secrecy. If there's anything to learn from our recent history and from other troubled times in American history, it's that secrecy and the erosion of accountability and quashing speech destroys our democracy and enables the worst kinds of abuses imaginable.

The intent of Anonymous is not evil, but it is morally murky. One reason the Civil Rights Movement was so powerful was that so many so intensely held to the principles expressed by Diane Nash: "Ends do not justify the means. As Gandhi said, everything is really a series of means."

Further Reading

In the last week, since I first started discussing this topic and writing about it, a number of other bloggers have written pieces that make similar or complimentary points. By no means a comprehensive list, here are some of the posts that I read along the way as I was working on this one:

- Josh Mull, Journalism is not an Attack, Wikileaks is not Warfare (Firedoglake)

- Tom Watson, Denial of Service, Denial of Speech

- Nancy Scola, Ten Ways to Think About DDoS Attacks and "Legitimate Civil Disobedience" (TechPresident)

- Nancy Scola, Some U.S. Political Tech Vets Don't Think Much of DDoS (TechPresident)