December 2005

Those of us who grew up in America’s traditional Black communities know of Watch Night Services, the gathering of the faithful in church on New Year's Eve. So as I ventured into the world it came as a surprise to me that other than the Catholic Church, which celebrates the eve of the feast of the Circumcision late on the evening of December 31, primarily white protestant churches generally do not have a church service for a secular holiday.

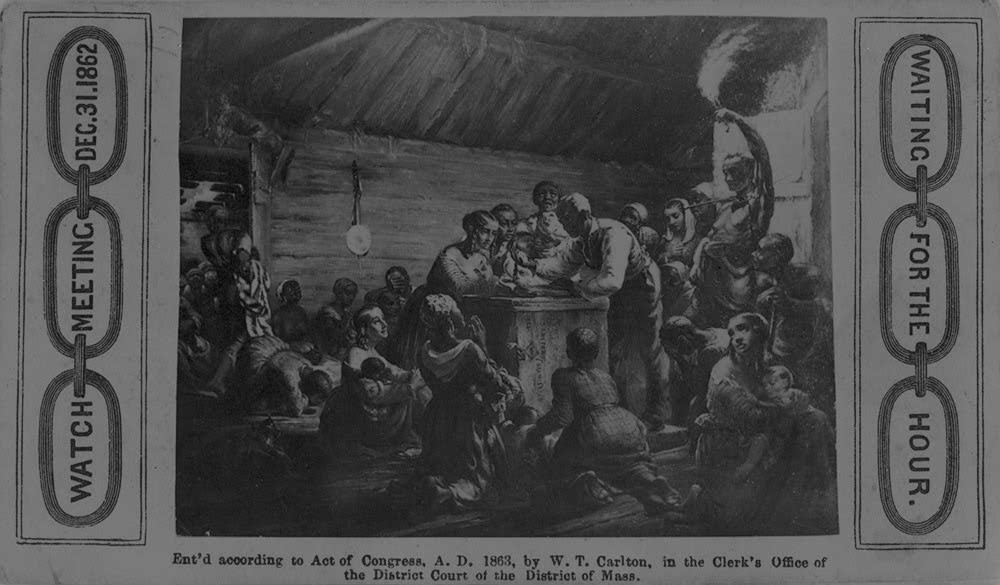

The service is an opportunity to tell the story of one of the most important milestones in the Blacks’ American history. The Watch Night Services that we celebrate in Black communities today can be traced back to gatherings on December 31, 1862, also known as Freedom's Eve. On that night, Blacks came together in churches and private homes, anxiously awaiting news that the Emancipation Proclamation actually had become law. Then, at the stroke of midnight, it was January 1, 1863, and all slaves in the Confederate States were declared legally free. Blacks have gathered in churches annually on New Year's Eve ever since, praising God for bringing us through another year.

Long before President Abraham Lincoln had ever dreamed of issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, an edict of freedom, Blacks had been hoping and praying for such a measure.

Lincoln had originally conceived of the proclamation as a measure for the self-preservation, rather than for the regeneration, of America. But the proclamation, almost in spite of its creator, changed the whole tone and character of the Civil War. Blacks sensed this more quickly than did Lincoln.

Despite the proclamation’s limitation African-Americans hailed it with much joy. The war, wrote Frederick Douglass, was now “invested with sanctity.” The Emancipation Proclamation did more than lift the war to the level of a crusade for human freedom. It brought some very substantial practical results, for it gave the go-ahead signal to the recruiting of Black soldiers. By midsummer of 1863 Lincoln could report, “The emancipation policy, and the use of colored troops, constitute the heaviest blow yet dealt to the rebellion.”

The esteem that African-Americans had for the Emancipation Proclamation helped to make it one of the most far-reaching pronouncements ever issued in the United States. African-Americans were instrumental in creating the image of the proclamation that was to become the historic milestone. The proclamation soon assumed the role that African-Americans had given it at the outset, and became to millions a fresh expression of one of humankind’s loftiest aspirations—the quest for freedom. The Emancipation Proclamation did not have to await the verdict of posterity: within six months after it was issued on that fateful date of January 1, 1863, the mass of Americans had come to regard it as a milestone in the long struggle for human rights.

“As affairs have turned, it is the central act of my administration, and the greatest event of the nineteenth century,” lamented Lincoln, as he sat in a pensive mood for is his portrait painter Francis B. Carpenter in February 1865. Later that spring, in the waning days of his life, in what was to be a rare moment of self-revelation, Lincoln confided to lifetime friend, Joshua F. Speed that he had come to believe that his chief claim to fame would rest upon the Proclamation. It was the one thing that would make people remember that he had lived.

Those of us who come from an oral tradition must tell this story in every generation; thus we celebrate the Watch Night Services.

~