Since the 2000 presidential election, there has been increased awareness of the disenfranchisement of ex-felons, which affects African Americans disproportionately. This was one of those issues that helped a lot of people see just how much racism has been at play in current electoral controversies. Whenever you think you're observing racism at play, it's good to start asking historical questions. The answers will often speak volumes about the current situation. Some initial digging about the historical roots of felony disenfranchisement is enough to make it clear that this form of disenfranchisement is right up there with things like voter intimidation as living vestiges of America's shameful Jim Crow system.

At the end of the Civil War, however, lawmakers found new uses for felony disenfranchisement laws. The newly adopted Fifteenth Amendment allowed African Americans to vote – in theory. In practice, Southern whites soon began to rewrite their state constitutions to remove African Americans from politics. Declaring proudly and explicitly their goal of white supremacy, these lawmakers used a variety of legal schemes to disempower African Americans, including literacy tests, poll taxes, grandfather clauses and all-white primaries. Most of these laws have been called out as racist and unconstitutional, and have been wiped from the books. Felony disenfranchisement laws are the notable exception.

Mississippi’s 1890 constitutional convention was among the first to use felon disenfranchisement laws against African Americans. Until then, Mississippi law disenfranchised those guilty of any crime. In 1890, however, the law was narrowed to exclude only those convicted of certain offenses – crimes of which African Americans were more often convicted than whites. The Mississippi Supreme Court in 1896 enumerated these crimes, confirming that the new constitution targeted those “convicted of bribery, burglary, theft, arson, obtaining money or goods under false pretenses, perjury, forgery, embezzlement or bigamy.”

Other states followed suit. Many newly disenfranchisable offenses, such as bigamy and vagrancy, were common among African Americans simply because of the dislocations of slavery and Reconstruction. Indeed, the laws were carefully designed by white men who understood how to apply criminal law in a discriminatory way: the Alabama judge who wrote that state’s new disenfranchisement language had decades of experience in a predominantly African-American district, and estimated that certain misdemeanor charges could be used to disqualify two-thirds of black voters.

“What is it we want to do?” asked John B. Knox, president of the Alabama convention of 1901. “Why, it is within the limits imposed by the Federal Constitution, to establish white supremacy in this State.” (Emphasis added)

Any discussion of remedy is, therefore, a discussion about whether we have the political will to undo institutionalized racism and fight its adherents.

So what about the Three-Fifths Clause? Well I was over at the National Voting Rights Institute (NVRI) website and discovered that felony disenfranchisement has some other dimensions that have not been part of the current discussions on election reform. NVRI has joined the Prison Policy Initiative in filing an amicus brief in Muntaqim v. Coombe, a case challenging New York's prisoner disenfranchisement laws under the Voting Rights Act.

So what about the Three-Fifths Clause? Well I was over at the National Voting Rights Institute (NVRI) website and discovered that felony disenfranchisement has some other dimensions that have not been part of the current discussions on election reform. NVRI has joined the Prison Policy Initiative in filing an amicus brief in Muntaqim v. Coombe, a case challenging New York's prisoner disenfranchisement laws under the Voting Rights Act.

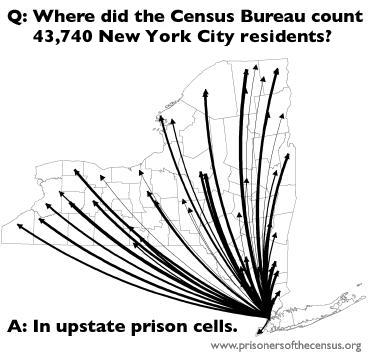

A combination of policies regarding the census, political redistricting and felon disenfranchisement are discriminating against racial minorities in New York state. The state denies incarcerated prisoners the right to vote, yet counts prisoners as residents of prisons where they are incarcerated when drawing its state legislative districts. This practice dilutes minority voting strength by enhancing the voting power of upstate rural prison districts, at the expense of the urban minority communities where most prisoners retain their legal residence. . . .

The brief explains how New York's policy of crediting prison towns with the presence of disenfranchised prisoners for purposes of redistricting enhances the voting strength of white communities that host prisons while diluting the representation afforded to urban communities of color. Representatives of these rural upstate districts make little pretense of treating prisoners as actual constituents.

State Senator Dale Volker, a conservative Republican who represents one such district, has acknowledged in an interview that he would sooner seek votes from the cows in his districts than from the prison inmates because "they would be more likely to vote for me." If prisoners were counted as residents of the communities where they resided prior to incarceration, rather than as residents of prison towns, a number of urban communities of color would in all likelihood be entitled to greater representation in the legislature. Several predominantly white upstate legislative districts would not have sufficient population to justify a representative were it not for the disenfranchised prisoners.

The brief points out that New York's assignment of disenfranchised prisoners to upstate rural districts for purposes of redistricting bears a striking resemblance to the original "Three-Fifths" clause of the United States Constitution, which allowed the South to obtain enhanced representation in Congress by counting disenfranchised slaves as three-fifths of a person for purposes of congressional apportionment. (Emphasis added.)

This disturbing combination of felony disenfranchisement law and census policy is not unique to New York State. So far, the Prison Policy Initiative has issued reports on the effects of such policies in fifteen states: Arizona, California, Florida, Idaho, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Montana. Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Texas.

The comparison between the function of the US prison system and our older, more explicitly racist laws should be enough to give readers pause. In honor of Black History Month, however, I will follow this post with two more to make a three part series. In Part 2, I will look further at the history of US racism to show what the structural purposes are behind many racist laws and policies. In Part 3, in light of the historical context in Part 2, I will look further at some of the implications and effects of miscounting prisoners. A brief review of the institutionalization of American racist ideology will show that though the implementation has changed, the basic structures upon which America was built remain very well intact.

Further Reading:

Prisoners of the Census

The Sentencing Project